History

The origins of the myths

The oldest proof of settlements in the municipal term come from Middle Palaeolithic, near the lighthouse dock. The Upper Paleolythic can be recognized in Morote and Palomas caves. Los Tollos, El Palomarica and Hernández Ros enclose some remains of the Solutrean ages. The Algarrobo cave harbours some remains of the upper Magdalenian and the Epipalaeolithic.

In the Eneolithic period, the most important site is Cabezo del Plomo, in the foothills of Sierra de las Moreras, closely related to the settlement of Los Milllares. The culture of El Argar has representative spots in Ifre, Cerrico Jardín, Las Toscas de María and Las Víboras.

Between Phoenicians and Romans

There are some archaeological spots from prerroman civilization, from the Phoenicians, found in Isla beach and Los Gavilanes. Here we can also find one of the most important remains of the subwater archaeology: two Phoenician ships 2600+ years aged.

Those remains put Mazarrón on the map of Phoenician trade in the Mediterranean Sea, between Ebusus (Ibiza) and Gadir (Cádiz), where Phoenicians probably settled attracted by the silver and lead strip minings in the area.

Thanks to a great deal of mining wealth in the region of Mazarrón and the vicinity of Carthago Nova, those remains will serve as a cathalyst for Roman colonization, showing archaeological remains of this period both in Loma de Sánchez and Coto Fortuna.

The Roman colonization will cover both I and II BC centuries, pumped up by mining, and enclosing numerous remains, especially in Los Cabezos de San Cristóbal and Perules (currently next to the city centre), as well as Coto Fortuna and Pedreras Viejas.

Due to the mining activities, a new form of metallurgical works arises, which can be seen in the remains of several ovens and fundry slags, being the most important one the Loma de las Herrerías.

The coastal area will increase in importance thanks to the ‘garum’ (some sort of fish sauce, to be exported all over the Roman Empire) manufacturing facilities, with remains of utmost importance in El Mojón, La Azohía, El Castellar and Puerto de Mazarrón.

Middle Age: one origin, three cultures

We do not have information of the Visigothic and Byzantine occupations, although we can deduce that mining activity would be present during both periods; however, the general state of insecurity in Spain leads us to deduce that there were no glory days for mining in Mazarrón.

In the Islamic Age, some strip mining was present in Cabezo de San Cristóbal. However, due to the bellicosity of this period, one can only think of a standstill in the economy of the whole municipality.

Once the Reign of Murcia was conquered in 1243, Mazarrón was incorporated into the Concejo of Lorca, a frontier area between the Reign of Murcia and the Nazari Realm, initiating a period of morisco raids and muslim incursions in the latter.

The Modern Age: the discovery of alum

Thanks to the occupation of Granada in 1492, the industrial reactivation in the whole Realm of Murcia rises again. Halfway to XV century, the alum is discovered, which consists of a mixture of alunite and potassium sulfide used to set colours on clothes and glass manufacturing, as well as in medicines, among other applications.

The vast amounts of alum available in the area gives rise to the name of the first housing settlement in Lorca, called ‘Casas de los Alumbres de Almazarrón’.

In 1462, Henry IV granted exclusive privilege of strip mining rights to Don Juan Pacheco, I Marquis of Villlena, who gave up the rights to Don Pedro Fajardo, Governor of the Realm of Murcia. Those nobles managed alum stripping in person or via leasing agreements.

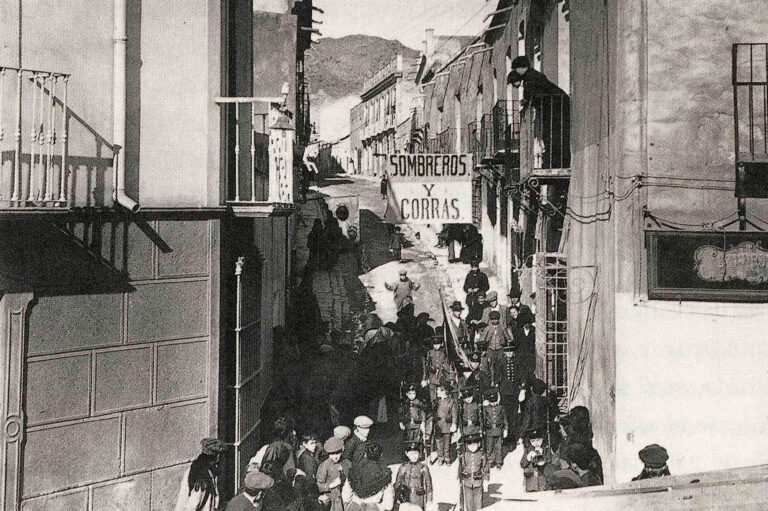

In 1572, thanks to the rise in alum mining, a permanent settlement in Cabezo de San Cristóbal was built, receiving from Felipe II its town hall title, which later became the independent Council of Lorca.

In late XVI century, decay in alum strip begins, due to italian exports, high taxes and the conflicts in Flanders and England, which led to the prohibition of exporting materials to those countries, the primary market for alum business of Mazarrón.

This booming in the economy can be seen in the character of Mazarrón in several buildings like San Andrés Church, built under the patronage of the Marquis of Villena; the Church of San Antonio, with Marquis of Vélez, as well as the Castillo de los Vélez, and the Church of the Purísima, a product of several historic stages, being the XVIII century the most important one, after the leasing to the Franciscans of San Pedro de Alcántara, that would also built a hospice and a convent near the site.

Once the alum strip mining was abandoned, the ‘almagra’ took its place in XVII and XVIII centuries. This material was used by the Real Hacienda to make arsenals, and was also manufactured to produce the famous red tobacco of Seville. Esparto for wires and ropes for ships were also manufactured. Mazarrón will rise again at the end of XIX century, with the exploitation of iron stripping and argentiferous galena.

The discovery of the ‘Prodigio’ seam was the main source of wealth for Mazarrón. One of the consequences of the rise in mining manufacturing was the enormous increase in population of Mazarrón, from the Andalusian region.

The introduction of the railway

The railway was a logistical support for the mining industry. In 1886 the Mazarrón-Puerto de Mazarrón line was opened, as well as other tracks to transport minerals from Morata to Parazuelos, where the material was stowed for transformation purposes. At the end of XIX century, Santa Elisa foundry was built, with state-of-the-art facilities.

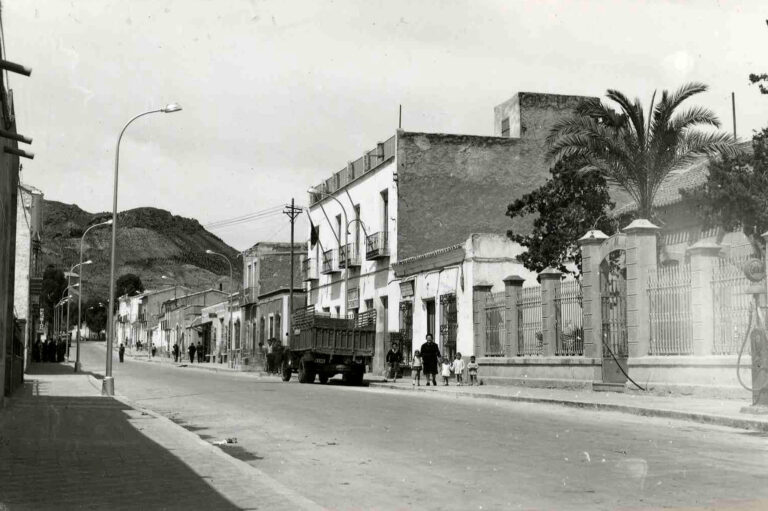

Apart from the exploitation of salines in Puerto de Mazarrón, fishing and non-irrigated land agriculture complemented mining in the area. Halfway to XX century, strip mining was almost abandoned, with a new economic reactivation in the 1970’s, thanks to intensive farming exploitation, mainly tomatoes in the winter season, and also with tourism.

Mazarrón today

Today, Mazarrón is one of the most attractive touristic spots in Spain, thanks to its idyllic, almost unspoilt landscapes, as well as an organic, environment-friendly development mixed with traditions, that allow visitors to enjoy the Mediterranean sea the same way our ancestors did.